When I was growing-up in North Devon, frequent trips to the seashore were aimed greatly at catching prawns and crabs for tea. But Dad also bought me a copy of Collins Pocket Guide to the Seashore and, in my teens, I started putting names to what I saw. I still have that annotated volume, although it bears the scars of being dropped in several rockpools. Meanwhile, in the public library at Ilfracombe, I discovered the writings of Philip Henry Gosse, the foremost Victorian marine naturalist who had made North Devon one of his favorite places. And, he had found CORALS – corals in British waters! Corals became a special fascination for me but I also re-visited the shores that Gosse had described to see if the same species could be found again 100+ years on – and they could. That activity of re-visiting locations to check if old records persist to the present continues today – although now I also look back at records that I made 40+ years ago.

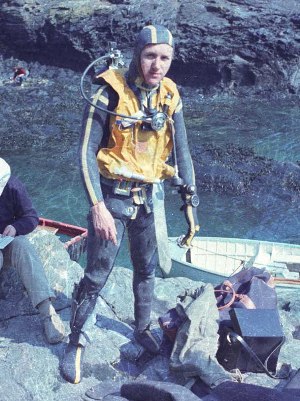

Keith circa 1969 and (above right) at Lundy in 2009 c.Neil Hope

Keith circa 1969 and (above right) at Lundy in 2009 c.Neil Hope

It was university that gave me so many opportunities to develop my interests in marine natural history. I was at Westfield College where our marine zoology classes included exams requiring ‘identify with reasons’: what a valuable way to learn. I was also fortunate to go on the tail-end of University of London field trips to the Isles of Scilly where I encountered taxonomists contributing to the Isles of Scilly Marine Fauna lists. And there were also expeditions to Lough Ine – where I learned the importance of careful and accurate identification and the proper record-keeping that Jack Kitching insisted on. I was also fortunate in my choice of PhD supervisor, topic and location (the Menai Bridge Laboratory of the University College of North Wales). I was supposed to be researching larval biology of hydrozoans but that wasn’t going well and I persuaded Denis Crisp that I should investigate the effects of water movement (tidal currents and wave action) on the ecology of sublittoral rocky areas. So, on with the diving gear and off to survey Lundy, Anglesey, Lough Ine and Abereiddy Quarry in Pembrokeshire (and to do cruel things to seabed species in a flume).

Now that I was an ‘expert’ in organizing surveys (!), I set about inviting taxonomic specialists to Lundy where I had started to record the character of the underwater marine life. The resulting fauna lists are available from www.lundy.org.uk.

Identifying what we found in those early days wasn’t easy. We did not have most of the identification guides and keys that weigh heavy on our bookshelves now. And, many of the texts that we were using were in French or German. By way of illustration, when I found a bright yellow coral at the Knoll Pins on Lundy in August 1969, it took until May the next year, searching papers and other sources and writing letters to specialists in Europe, before I found that it was Leptopsammia pruvoti – a very common species in the Mediterranean; but mine turned out to be the first record for Britain. Now, open any one of many identification guides in English, and there it will be.

Marine survey work, for me, ‘took-off’ in the mid-70s when the Nature Conservancy Council ‘discovered’ marine conservation and Roger Mitchell started to commission work that would document the marine life of intertidal and subtidal areas around Britain. At the time, I was employed by the Field Studies Council Oil Pollution Research Unit where much of the work involved grab sampling in the North Sea and meticulously identifying the taxa from the grabs. However, I was rocky shores and surveys that involved diving. We were working with check lists of conspicuous species and not getting involved in detail in any particular group. Our work, and subsequently that which was undertaken by the Marine Nature Conservation Review of Great Britain (MNCR), provides the core of information to characterize locations and identify those that at are special. The MNCR started in 1987 and the Advanced Revelation database that was to store the results of surveys was the starting-point for what eventually was to become a very large part of the Marine Recorder resource. The MNCR was never completed and there remain major gaps in our knowledge of what’s where that will only be filled in a way that is relevant to biodiversity conservation if in situ surveys of species are carried-out by trained and experienced marine biologist surveyors – yes, I’m trying again to get a message across to those who think acoustic surveys or just identifying biotopes will do the job – they will not.

Marine survey work, for me, ‘took-off’ in the mid-70s when the Nature Conservancy Council ‘discovered’ marine conservation and Roger Mitchell started to commission work that would document the marine life of intertidal and subtidal areas around Britain. At the time, I was employed by the Field Studies Council Oil Pollution Research Unit where much of the work involved grab sampling in the North Sea and meticulously identifying the taxa from the grabs. However, I was rocky shores and surveys that involved diving. We were working with check lists of conspicuous species and not getting involved in detail in any particular group. Our work, and subsequently that which was undertaken by the Marine Nature Conservation Review of Great Britain (MNCR), provides the core of information to characterize locations and identify those that at are special. The MNCR started in 1987 and the Advanced Revelation database that was to store the results of surveys was the starting-point for what eventually was to become a very large part of the Marine Recorder resource. The MNCR was never completed and there remain major gaps in our knowledge of what’s where that will only be filled in a way that is relevant to biodiversity conservation if in situ surveys of species are carried-out by trained and experienced marine biologist surveyors – yes, I’m trying again to get a message across to those who think acoustic surveys or just identifying biotopes will do the job – they will not.

In 1998, I started work in Plymouth with the Marine Biological Association (MBA) to establish what became the Marine Life Information Network for Britain and Ireland (MarLIN). The following ten years or so were formative for marine recording with the NBN of central importance – although a very different beast today compared with what it was in 1998. We contributed to that development and the MBA now provides the marine node for the NBN and is the Marine Environment Data and Information Network (MEDIN) accredited data archive centre for marine species and habitats. But, I retired in 2008 and, although still involved in research as an Associate Fellow at the MBA, my recording is mainly via hobby rockpooling and recreational diving including participating in Seasearch.

In 1998, I started work in Plymouth with the Marine Biological Association (MBA) to establish what became the Marine Life Information Network for Britain and Ireland (MarLIN). The following ten years or so were formative for marine recording with the NBN of central importance – although a very different beast today compared with what it was in 1998. We contributed to that development and the MBA now provides the marine node for the NBN and is the Marine Environment Data and Information Network (MEDIN) accredited data archive centre for marine species and habitats. But, I retired in 2008 and, although still involved in research as an Associate Fellow at the MBA, my recording is mainly via hobby rockpooling and recreational diving including participating in Seasearch.

My marine life recording has always been driven by curiosity and especially looking for patterns in the distribution and abundance of species. Three passions – marine ecology, photography and diving – have been central to what I have done and am still doing. Highlights occur every-so-often and include finding locations with fabulously rich communities or stashed full of rare and scarce species. A recent highlight was when an ovulid sea snail that seemed ‘different’ to a species I had been asked to collect by a specialist turned-out to be new to science: Simnia hiscocki Lorenz & Melaun.

Finally, some confessions. I am no taxonomic specialist – I am a generalist where identifying species is a means to an end: understanding patterns and change in marine ecosystems. I don’t submit enough records! I see unusual species and mean to do it (and occasionally do) – but not enough. I don’t have the sharp eye that many amateur naturalists have but I am therefore well-placed to make the point that there are rockpoolers and divers out there who do not have a string of degrees but still have the opportunity and skills to point-out species that are unusual or different and, well, you never know where that will take you.