Over the past few weeks the five Identification Trainers for the Future have been busy working at our Museum curation placements, with each of us having chosen a subject we wanted to work on in more depth.

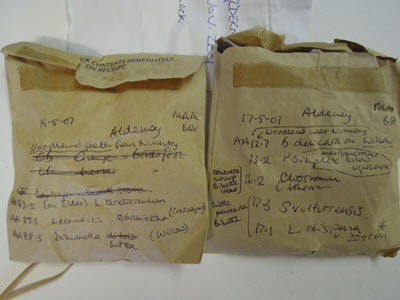

My placement is with the lichens department, under the supervision of lichenologists Holger Thus and Pat Wolseley. I began with barcoding Cladonia lichen specimens collected in southern England. I then added their label details to a database, ready for an upcoming project by a researcher from Portugal. Since then I have been working through a collection donated to the Museum by two respected lichenologists, Ann Allen and Barbara Hilton. So far I have catalogued the label data for specimens from the Scilly Isles and the Channel Islands. This largely involves deciphering handwriting and field notes, checking if the names are those in current use, checking specimens in paper packages and noting if these are suitable for inclusion in the main collection, as well as any problems with the data or specimen. This can be a challenge, with some specimens consisting of just fragments of a few minute apothecia (fruiting bodies) that have been scraped from a coastal rock and wrapped in a scrap of tissue paper. On the other hand, now and again I come across a beautiful specimen, such as a fine Cladonia pocillum with its pixie-cup podetia intact and surrounded by picturesque green moss. This impression of an intricate, hidden, miniature world is what drew me to lichens in the first place. Of course this is a valuable learning opportunity for me and I am quickly getting used to the names of the more obscure genera and their physical appearance, as well as learning the associations between each collected species and its habitat, so diligently noted on the paper packages.

Jas is working with Hymenoptera curator Gavin Broad, looking at parasitoid wasps. I get the impression that this is a dream come true for him! He has been busily re-curating drawers of Ophion Ichneumons (a group of rather elegant, nocturnal, orange-red wasps), removing them from their original cork-based drawers to a more suitable home. He says, “There is also the possibility that a particular species belonging to the genera Ophion may be more than one species and I have been asked to examine this exciting taxonomic problem as I re-curate the collection.” The photo shows a delicate Ophion specimen collected in 1871 and still in fine condition.

Krisztina is spending her curatorial placement focusing on her favourite subject- bees – under the supervision of David Notton. She has been working on 12 trays of unincorporated Bombus species from the collection. Her aim is to try to identify, organise and re-curate them. She tells me that this has been undoubtedly the biggest challenge and the best opportunity so far that she has encountered as an ID Trainer. Most of these bumblebees are close to being 80-100 years old; their banding and colouration has faded and quite a few of them are missing some body parts and hairs, which makes identification even more difficult! During this month she has already come across some rare Bombus species such as Bombus distinguendus, the Great Yellow Bumblebee, which is now confined to the Outer Hebrides. Apart from the scarce species, she tells me that “Other fascinating finds were specimens of Bombus muscorum from the Aran islands which display colour variations that are different from the mainland form. This bumblebee has black-haired abdominal tergites which makes this species resemble more a buff-tailed B. hypnorum. These island populations have been given subspecific status, in this case of the Aran islands it is called Bombus muscorum ssp. allenellus.”

Niki is clearly drawn to the Lepidoptera department like a Feathered Ranunculus to a light trap. She writes: “I am having an amazing time getting to work with an exceptionally knowledgeable and welcoming team! As part of this I am lucky enough to be working on the British and Irish Lepidoptera collections of Dr EA Cockayne, Dr HBD Kettlewell and Lord Walter Rothschild, to name but a few. My current role within the team is to assist with the re-curation of the British and Irish Noctuid Moths in preparation for their digitisation. Firstly I must find the required species, as outlined in the Agassiz checklist (the most up to date taxonomy), in the vast museum collections. This is a fantastic job because I get to know my way around the collections and I get to see many species, which is helping no end with my identification skills. After finding the specimens I must ensure they are all labelled correctly, adding accession labels where necessary. Finally, the specimens are rehoused into new plastazote-lined drawers which are much better at protecting the specimens from damage than the old cork-lined drawers. Of all the species I have worked on so far I have particularly enjoyed the Plusiinae moths, with one of my favourite species being the Spectacle (Abrostola tripartita). This moth gets its name because of the scales on the front of the thorax which resemble a pair of spectacles (as you can see from the photo below). One of the best things about my current role is getting the opportunity to see a great number of the same species, giving me the opportunity to get to know aberrations within that species. I am also able to compare similar species to gain a greater understanding of the differences. I feel my moth identification skills have already come on leaps and bounds and I still have two months left!”

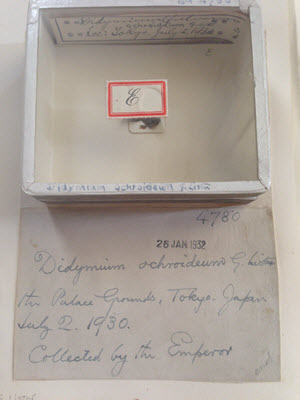

Sophie knew from day one that the mysterious and under-studied slime moulds were what she wanted to look into further. She tells me that for her curatorial placement she has been working on cataloguing the type specimens of slime moulds. Types are the specimens that are described and used to define a species and she has been working through the Museum’s whole collection. Her favourite find so far is a type which was collected by The Emperor of Japan in 1930. She says, “I later found that there were several specimens collected by the Emperor who was interested in slime moulds and presented several specimens to The British Museum. I am looking forward to digitising the notebooks of Lister, who was the leading expert in the UK for slime moulds at the time, and reading the correspondence she had with the Emperor of Japan as well as seeing the beautiful artwork she created.”

It hasn’t only been about curation placements since the end of August, with trainees involved in helping at taster days for those interested in becoming next year’s trainees. We inevitably have mixed emotions about this because, while we are happy to see so much enthusiasm for nature and recording, it is a clear reminder that we don’t have very long left with our placements and must make the most of every moment we have here!

I attended Science Uncovered at the Museum last year as an Identification Trainer hopeful, and I remember being impressed by last year’s trainees and their table displays. Well, this year it was our turn to engage the public and we had a great evening, although it was so busy I didn’t get a chance to look at any other displays! We all did a display based on our curation placement, with interesting specimens to hand for people to look at. Lots of enthusiastic members of the public –including people applying for next year’s Identification Trainers programme – came along to ask questions and look through the microscopes. I talked about lichens and pollution, and how the pollution mix was changing, with much less atmospheric sulphur dioxide now but high levels of nitrogen dioxide, and what that meant for lichens. I also demonstrated chemical spot tests for lichen identification, with the example of potassium hydroxide – when added to yellow Xanthoria lichens it turns blood red and is a striking example to show people. Visitors from Bulgaria, Canada, Indonesia, Italy and the Philippines were amongst those who chatted with me and the sense I got was that information on lichens was somewhat hard to come by for many people. There was certainly a real curiosity and desire to learn more about lichens and how the species mix is changing, and what this tells us about our environment.

I could see the other trainees were equally busy and enjoying their evening too, with plenty of interaction with visitors. For example, Jas engaged the public with his knowledge of parasitoid wasps (Ichneumonidae) and he says that people were really fascinated by the behaviour and strategies used by parasitoids to find hosts to lay their eggs on or in. He adds, “The people who attended were from a very wide variety of backgrounds, from members of the public just generally interested in natural history to researchers from Imperial College, so different levels of engagement were required for different attendees – really enjoyable!”

Coming up soon we have Nature in Parliament Day with the NBN and part two of a bioblitz documentary, featuring Chris Packham, amongst other events. The pace of the traineeship shows no signs of letting up at this stage – and that’s fine by us!

Written by Joe Beale