The Network then and now

The data

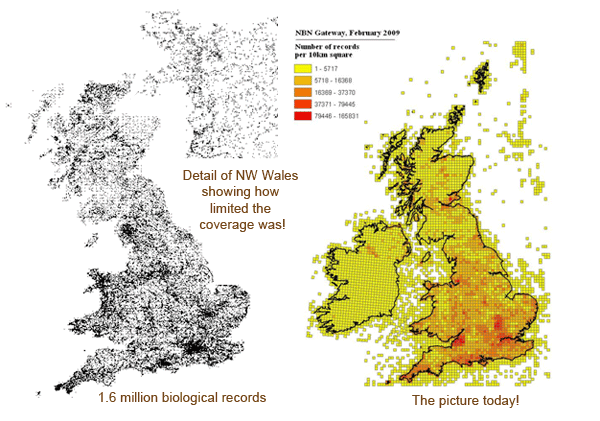

On the 3rd April 2000 the National Biodiversity Network Trust was incorporated as a company limited by guarantee; on the 25th August it became a registered charity. In February of the following year there was a ‘celebratory launch’ at the Linnean Society, where the mark one NBN Gateway was revealed to an expectant audience that included the then Minister, Michael Meacher. As I recall, we made available 1.6 million records from 4 or 5 datasets. The illustrations show the coverage, with each black spot being a record. The close up of NW Wales shows just how sparse the coverage was at the time. But images such as this, and the promise of realising the dream, so vividly painted in the Coordinating Commission for Biological Recording’s (CCBR) report of 1995, of improving access to the tens of millions of biological records that were known to exist, led to the funding needed to take us through to the 50 million records available today, and the NBN Partnership encompassing all aspects of biological recording in the UK.

It is easy to dwell on the hard facts that underlined the achievements to date; 50 million biological records available on the NBN Gateway that can be viewed by anyone in the world let alone the UK, over 400 datasets covering 40,161 species ( not including the so called micro-species) , 150 – 200,000 hits per month on the NBN Gateway.

The technology

The Species Dictionary, which provides the taxonomy underpinning of the NBN Gateway, is built from a series of checklists, supplied by national recording schemes, statutory bodies and other authoritative sources. The contents have grown considerably over the years; in 2000 there were 183 checklists containing 235,400 records of 95,700 names. At the beginning of 2010 there are 310 checklists containing 675,600 records of 251,500 names. Given that there are about 80,000 species in the UK (excluding Viruses and Bacteria); the apparent excess number of names is due to obsolete names, variant spellings – and vernacular names. The Species Dictionary ensures that all variant names are mapped to recommended scientific names; any user of the NBN does not need to be concerned about these variations when they run a search for a particular species, the system takes care of that. The Species Dictionary provides full coverage for 80% of taxonomic groups with only 7 (out of 110) groups having no coverage. This makes the Dictionary the most comprehensive source of biological names in the UK, and makes the UK one of the best studied regions in the world. And let us not forget that both the NBN Gateway and Species Dictionary are shared internationally. Publically viewable data from the Gateway and Dictionary is shared with the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). Data from the Dictionary also feeds into the Pan-European Species-directories Infrastructure.

The people

The facts are impressive, but I think the biggest success has been the partnership itself. There are over 120 organisations sharing data through the NBN Gateway! This includes national recording schemes, local record centres, central government, public agencies and institutions, national societies, commercial companies, voluntary organisations, and scientific associations. 100 individuals, from across the Biodiversity Community, help maintain the quality of the data available from the Species Dictionary.

First meeting of the NBN Trust – From left to right: Top row: Jim Munford, Deryck Steer, Mark Avery, Andy Brown, Trevor James, Mike Roberts, John Seager. Front row: Jo Purdy, the late Sir John Burnett, Sara Hawkswell and Johannes Vogel

The idea of a national network for sharing biological records is not new; it did not begin with the NBN. At our last conference the Trust awarded its Honorary Membership to Prof. Sam Berry. Sam was not the only person to play a significant part in the long history leading up to the formation of the NBN Trust, but his association can be traced right back to the early stirrings of the idea. If a date needs to be set for the NBN’s conception, we need to go back to at least the September of 1984 and the Biology Curators’ Group hosted seminar Biological recording and the use of site based biological information. Its conclusions on the funding and organisation of biological recording were followed up during and after Sam’s final year as President of the Linnean Society. A small working party produced the report Biological Survey, Need and Network published in 1988. Included in its conclusions was the recommendation that a co-ordinating commission be created to plan and establish a national, computerised system, and to investigate related issues such as the statutory and legal framework. This report was followed by a meeting of interested organisations and institutions hosted by NERC at the Royal Society in February 1989. This meeting led directly to the establishment of the CCBR under the chairmanship of the late Sir John Burnett, who was to be the NBN Trust’s first chairman. This brief history is dotted with others who have received the Trust’s Honorary Membership; Paul Harding who has championed the NBN from its early days to the present, the late and much lamented Charlie Copp creator of the NBN data model, and Trevor James, who has played his part as a Trustee of the NBN Trust, manager of Hertfordshire LERC, chairman of the NFBR, employee of the NBN Trust and (very) active recorder.

The idea of a national network for sharing biological records is not new; it did not begin with the NBN. At our last conference the Trust awarded its Honorary Membership to Prof. Sam Berry. Sam was not the only person to play a significant part in the long history leading up to the formation of the NBN Trust, but his association can be traced right back to the early stirrings of the idea. If a date needs to be set for the NBN’s conception, we need to go back to at least the September of 1984 and the Biology Curators’ Group hosted seminar Biological recording and the use of site based biological information. Its conclusions on the funding and organisation of biological recording were followed up during and after Sam’s final year as President of the Linnean Society. A small working party produced the report Biological Survey, Need and Network published in 1988. Included in its conclusions was the recommendation that a co-ordinating commission be created to plan and establish a national, computerised system, and to investigate related issues such as the statutory and legal framework. This report was followed by a meeting of interested organisations and institutions hosted by NERC at the Royal Society in February 1989. This meeting led directly to the establishment of the CCBR under the chairmanship of the late Sir John Burnett, who was to be the NBN Trust’s first chairman. This brief history is dotted with others who have received the Trust’s Honorary Membership; Paul Harding who has championed the NBN from its early days to the present, the late and much lamented Charlie Copp creator of the NBN data model, and Trevor James, who has played his part as a Trustee of the NBN Trust, manager of Hertfordshire LERC, chairman of the NFBR, employee of the NBN Trust and (very) active recorder.

The recipe for success

I have a deep and abiding suspicion that we were not expected to succeed; my secondment as Programme Director of the NBN was originally for two years! I am still here, albeit as Chief Executive and, more importantly, so is the NBN. So what made the difference? Why after 15 years of talking, thinking and reporting did the NBN come to life, and why has it succeeded?

I think part of the answer must lie in technology; the development of computing, electronic databases and the Internet. Without these ingredients the NBN as a mechanism for sharing biological records could not function. In terms of technology, the time was right.

But there is another factor, a human factor. Biological recording in the UK has such a long tradition. For more than 150 years groups of recorders (particularly botanists) with a shared interest in one taxon or another have come together to exchange records, to learn from each other, to become guardians of the quality of the records they have gathered, and to publish their results. When I took up my post as Programme Director I made a guess; I thought that the technical issues could be brought to a (first) resolution within two years, given that in fact the technical development never actually stops, as the underlying technology is evolving and we must keep pace. I thought, realistically, it could take up to 15 years before we saw any major acceptance of the concept of a network – how wrong I was. There would always be, what I believe are called, early adopters, those at the head of the queue for the new i-phone or blu-ray player! Our early adopters came through the Biological Records Centre, then based at Monks Wood. Those early data sets included dragonflies, carabid ground beetles, bryophytes, freshwater crayfish and a marine dataset – a pretty eclectic mix! I remember the first big jump in numbers came when the Botanical Society of the British Isles let us share their data, which pushed the numbers up considerably. What has happened since would have been unbelievable in those early days. By the launch of version 3 of the Gateway in 2004 we had reached 15 million records – the rest as they say is history.

We have tried to be inclusive; at one stage the NBN seemed to be about committees – thank you chairmen and women! The NBN is not about the NBN Gateway and the new technology, it is about data sharing, it is about ensuring that the NBN, the recorders, the national societies, the recording schemes and the local record centres, are valued and the biological records are used. A boost to local record centres came very early on in the life of the NBN Trust. Using funding from the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, secured by The Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts (then the RSNC), manuals on setting up and developing local record centres were published, and three new model local record centres set up. Funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and again the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, allowed the Trust to employ staff to work with the national schemes and societies and local record centres to help with funding, promotion and the technological challenges. The variability between national societies has always been a challenge for us; where is the commonality between the flea recording scheme and RSPB (Bob George – another Honorary Member, Ellen Wilson – who has served the NBN as a committee members and Trustee): all valued contributors of data – and valued for the support they have given to the concept of a network.

We sought all views when we drew up the seven principles for data exchange, and they have stood the test of time. The NBN is respected globally for the work we have collectively achieved in setting the standards that underpin the NBN; nomenclature through the NBN species dictionary, the exchange principles, the data exchange standards, metadata and now our latest challenges data flow principles and data quality criteria. These have helped to build upon the bedrock upon which the NBN stands.

For the true bedrock, let us return to that human factor. I have no idea how many biological recorders there are in the UK. The CCBR reported that there were 60,000, the RSPB reports that almost 500,000 people participate in their Big Garden Birdwatch. Whatever the true number, each one of those 50 million records now available through the NBN represents someone’s personal effort; to learn about recording techniques, to become familiar with the taxonomic skills they will need, to get to the survey site, to obtain permission to record on the chosen site, to seek out their specimens, to identify each one, to mark up a record card, to transcribe their record to a database, to pass those individual records on to a vice county recorder, or a scheme organiser, or a local record centre, perhaps to seek others views on hard to identify species and let us remember that at least 70% of all recording is by voluntary effort.

Thank you all for creating this enduring success – this is your legacy.

James Munford – Chief Executive