Written by John Sawyer, CEO, NBN Trust

Tim Berners-Lee summed up a large part of what the National Biodiversity Network is about in this single quote made late last year. Sharing data helps maximise its use in ways that we cannot imagine, to create a treasure trove from our data, not a hoard. The principle reason to do so is to help us achieve a wide range of positive environmental and social outcomes. Not to share is to undermine our Network’s raison d'être and many of our shared objectives.

Why share? The most compelling reason for us all to share our biological data and information is the current biodiversity crisis. As Achim Steiner – Director of the UN Environment Programme said in 2012: We haven’t even begun to understand the damage we are bringing to bear on the sustainability of our planet. If we, the experts, amateurs and engaged, don’t inform the debate about biodiversity through sharing our data how can we expect to halt its decline?

We must also share data so that we can achieve, as close as possible, an all-taxa view of biodiversity in the UK. An average species page on the NBN Gateway holds data from 12 different organisations and data providers. That is quite an achievement, but there is still plenty of work to be done. The NBN Gateway holds no data for 37% of all taxa (29,000+ taxa) and our data holdings are skewed in favour of 6300 taxa each of which has more than 1000 records. It is like attempting to monitor and understand the scale of an iceberg through looking solely at its tip.

We also share data in order to achieve a more complete geographic coverage in our biological data. The number of species records on the NBN Gateway per 10km Grid Square across the UK shows a general pattern with the number reducing as population declines northwards. Rotherham (SK49) is the grid square with the most records (more than 800,000) whilst grid square NB33, to the west of Stornoway on Lewis has just 1207. Plugging these geographic gaps means collecting and sharing data from every corner of the UK.

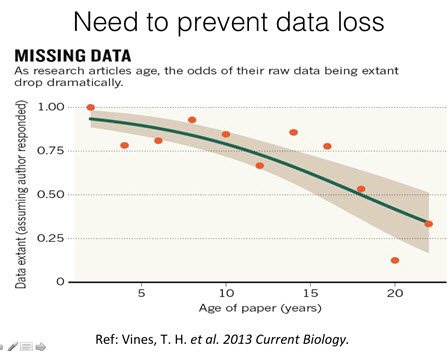

Figure 1: Data extinction as age of research data increases (from Vines et al. 2013)

Sharing data will help prevent data extinction. Research published two years ago (Vines et al. 2013) showed that 80% of research data has gone extinct or is unavailable after 20 years (see Fig 1). That is because the data is on storage systems that are now incompatible, the data have been destroyed or the researcher has moved on or died amongst other reasons. We must prevent this data loss.

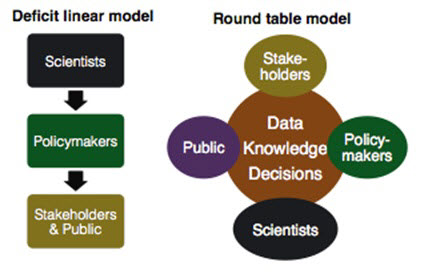

Sharing data helps improve decision-making. As Soranno et al. explained in their 2014 paper, the traditional deficit linear model of decision-making is where scientists or citizen scientists collect data, analyse them and hand it to policy-makers who then provide the public with the results. This is an abracadabra moment and often the public cannot see the evidence (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Deficit linear and round table models of decision-making (from Soranno et al. 2014)

They proposed a round table approach as a more powerful decision-making model (see Figure 2). That is when we all share our data and knowledge and make joint decisions based on what we all know. This provides for innovation and collaboration and deep understanding about how decisions were made. This would be near impossible without shared data.

Sharing data will help us achieve core environmental objectives. A good example is the management of invasive non-native species. One in five records of invasive non-native species on the NBN Gateway are currently hidden from view. Hiding data for species that can cause ecological or economic harm will impact detrimentally on our ability to manage these species.

We often hear about the need to teach and inspire younger generations, and new demographics, about biodiversity. If we are serious about educating and informing it means making data and information visible and usable. Expectations are high amongst younger generations that data will be discoverable. Why would we want to hide data and information from this new computer literate generation?

Sharing data will help government do their job more effectively and inform national policy and strategy. Collaboration in this way will help our network secure long-term support and resources. We must make ourselves indispensable through sharing our knowledge to help government, not the opposite.

Not sharing data would be an affront to most of the volunteers that collected it. There is an expectation that we are collaborating to maximise the use of citizen science data to good effect. We must make the most of the time and skills that volunteers are generous enough to donate.

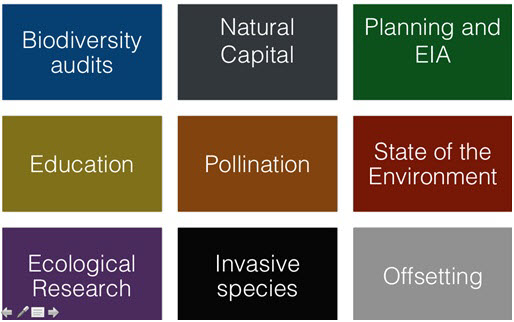

Figure 3: Uses for biological data shared by members of the National Biodiversity Network.

Finally, sharing data will help us maximise its use. Our collective data should be available for daily planning applications and environmental impact assessments, for the management of invasive species populations and improving conservation management (see Figure 3). We want to determine the changing state of our natural environment, educate people about nature, inform ecological research as well as understand changes in pollination services.

Conclusions Working together, the National Biodiversity Network, can provide a comprehensive, unparalleled and authoritative understanding of our natural world that can be used to educate and inform.

As Patricia Soranno et al. stated in their paper in 2014: ‘If environmental science is to be truly inclusive it is not only necessary to share, it is ethically obligatory’.

The new vision for the NBN is that: Biological data collected and shared openly by the Network are central to the UK’s learning and understanding of its biodiversity and are critical to all decision-making about nature and the environment.

We must maximise the use of data by continuing to share, to do otherwise would undermine our credibility, our usefulness and in many cases the objectives and visions of our respective organisations. It would also damage the unwritten contract, we have with our legions of volunteers, that we will endeavour to make the most of their time and effort and longstanding commitment to citizen observation across the UK.

References Soranno et al. 2014. Its good to share: Why Environmental Scientists’ Ethics are out of date. BioScience. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu169

Vines, T. H. et al. 2013. The availability of research data declines rapidly with article age. Current Biology 24, 94-97. DOI

This article is based on presentations given by John Sawyer at the 20th anniversary of the Centre for Environmental Data and Recording (CEDaR) on Sat 21 March 2015 at the Ulster Museum, Belfast and at the Scottish Biodiversity Information Forum Spring Conference on 16 April 2015 in Battleby, Perthshire. It is a follow-up to the article by Georgina Montgomery et al. in eNews in January 2015 entitled Sharing: More than Simply Playing Nice.