Written by Dr Adrian Cooper

This discussion is presented in five parts. First, I will summarize the principal features of collaborative map making, sometimes known as re-mapping. Second, I will outline the main features of liminal and therapeutic ecosystems. Third, I will review the motivation of citizen scientists from Felixstowe, Suffolk, who have been developing a collaborative map making approach to the River Deben Estuary. Fourth, I will discuss how the ideas of those citizen scientists have evolved since their early inception during the summer of 2024. Finally, I will discuss the questions on this subject which occupy the attention of these citizen scientists at the time of writing.

The authors of the collaborative map-making under review in this discussion are the Felixstowe Citizen Science Group (FCSG). They were established in April 2018 with the primary aim of conducting impact analyses on the work of their local wildlife conservation group called the Felixstowe Community Nature Reserve. Beyond that primary role however, FCSG members choose additional projects, one of which addresses the need to re-map local environments in order to encourage other local people to engage in new ways with those areas. Examples of other collaborative map making exercises which have been developed by FCSG include work on areas of local woodland called Newbourne Springs and Abbey Grove. The ways in which FCSG defines itself as a learning organization are discussed here.

The River Deben Estuary at Felixstowe is a tidal estuary with wide mud flats and salt marshes. It is a Special Protection Area (SPA), and a Ramsar site featuring redshank, avocet and curlew. Flora includes sea lavender, samphire, and sea aster.

Part 1

The principal features of collaborative map-making may be summarized as:

(i) It aims to create new maps by citizen scientists which include the types of data and information which are of interest to those groups and individuals.

(ii) Collaborative map making is therefore a form of democratic and non-elitist engagement with conservation spaces and other environments. It can be regarded as an example of social and geographical inclusiveness.

(iii) Collaborative map making does not seek to replace mainstream maps, such as those produced by the Ordnance Survey. Instead, it aims to produce a diversity of maps.

(iv) The process of collaborative map making begins where groups of map makers walk the area they wish to re-map. In doing so, they take notes on the features which they wish to include in their maps. Discussions then take place on how the diversity of data and information can be organized into a coherent map. Several drafts of maps are produced which may be shared with family, friends or on social media. Walking is therefore shown to be fundamental to the development of local knowledge and memories (Tuan 1974; Solnit 2001; Macfarlane 2012 and 2015). Data quality and other data management questions are discussed here.

(v) The final maps usually contain features which surprise readers who are familiar only with traditional maps. Recent examples of such surprising data from FCSG include sight data (eg bird species in specific seasons),sound data (eg the sound of waves, breeze, families, fauna etc); touch data (eg the experience which is often enjoyed by young people of running their finger tips over natural surfaces), taste data (eg recalling memorable picnics or other meals in the site to be mapped, or natural fruits having been picked) and fragrance data (eg the scent of woodland shortly after a rain shower, or the salty aroma of a river estuary).

(vi) Maps must evolve, otherwise they become redundant. Collaborative maps are no exception. Consequently, through discussion, reflection and feedback from other observers, collaborative maps become re-worked. Equally, it has been found that collaborative maps change with the seasons and also with political decisions (eg planning decisions to build housing on greatly appreciated natural habitats).

(vii) Collaborative maps are often experimental. The data and information contained in them are propositions to their readers to see what is helpful and stimulating, and what needs further development. In this way, collaborative maps are provisional: often in continual development, constantly under review and the subject of discussion (as all maps should be).

(viii) Given all the above points, collaborative maps may often surprise their readers. They will also disrupt readers’ expectations about what maps can be.

(ix) Despite their innovative nature, collaborative maps can still be located within an understanding of cartography as an Art, Science and Technology.

Part 2

Liminal landscapes can be understood as physical spaces or environments that exist in transitional or in-between states. The term “liminal” comes from the Latin word limen, meaning “threshold.” In this context, liminal landscapes are spaces that are neither fully one thing nor another, but instead exist in a state of transition, ambiguity, or flux (Shields, 2002; and Andrews and Roberts, 2014). In the context of the River Deben Estuary at Felixstowe, it is liminal as a consequence of its tidal, seasonal and weather patterns. From their interviews with local people, FCSG has identified four principal features of liminal landscapes:

(i) Transitional spaces: Liminal landscapes are often places where movement occurs from one state to another. Examples include estuarine mud which becomes covered with sea water during tidal change.

(ii) Psychological or emotional significance: Liminal landscapes are often linked with feelings of uncertainty, unease, or introspection because they represent a departure from the familiar. People might experience a sense of dislocation or transformation when encountering these spaces.

(iii) Ambiguous identity: Liminal landscapes might not fit neatly into any particular category or definition. For example, estuarine mud is neither completely land, nor is it fully river. That is, boundaries in physical form are blurred between natural states.

(iv) Temporal flux: Liminal landscapes often change over time or are associated with change. A river estuary is therefore an example of a liminal environment because it is always in a state of flux: caught between its tidal ranges.

The main features of therapeutic ecosystems have been discussed in Cooper (2000, 2019 and 2020). They may be summarized as follows:

(i) They can be calming and restorative. In doing so, therapeutic environments can help to lower blood pressure and encourage reflection / mindfulness. This aspect of therapeutic environments is closely aligned with the Japanese concept of shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing” where an emphasis is placed on immersion in nature and its restorative benefits.

(ii) Inspirational and uplifting / dynamic and energizing. This aspect of therapeutic environments is found where places inspire creativity such as writing, art, music composition or scientific investigation.

(iii) Redemptive / transformational. Here, environments can inspire a sense of renewed purpose. Sometimes this might be described as redemptive, or even healing eg after trauma or loss.

(iv) Grounding / centering. Therapeutic environments can provoke a sense of stability and connection with broader themes within the natural world, fostering resilience and balance.

(v) Socially inclusive and supportive. These features of therapeutic environments are experienced where locations have facilities which encourage social interaction. In doing so, those experiences can help to alleviate loneliness and improve mental well-being by fostering a sense of belonging to a location.

(vi) Escapism: These experiences of therapeutic environments can provide a sense of temporary relief from the challenges of daily life, allowing people to step outside their routine context and anxieties.

(vii) Mystical / spiritual: Here, landscapes can inspire deep reflection and even profound existential insight. The work of John Muir and Henry David Thoreau include examples of this aspect of therapeutic environments.

Given this context, therapeutic ecosystems can be thought of as a form of sanctuary. In recognizing this, it follows that environmental sanctuaries have two main features: (i) as a sanctuary from challenging problems such as family, work, debt, anxieties, stress; (ii) as sanctuaries within which creativity can be developed either as an artistic or scientific body of work.

Part 3

The motivation of FCSG members to create their own maps of the River Deben Estuary at Felixstowe may be summarized as follows:

(i) The estuary is a completely different type of environment to the woodland areas which had been previously re-mapped by FCSG.

(ii) Re-mapping the Deben Estuary gave FCSG members an opportunity to engage with a liminal ecosystem, the nature of which is summarized above.

(iii) The re-mapping exercise also provided FCSG members with an opportunity to re-map the Deben Estuary as a therapeutic environment. This was of particular interest to those members of FCSG who identify as people of faith. In doing so, those individuals have developed the notion of the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe as a local pilgrimage destination. That is, although it is clearly not a traditional pilgrimage location, it still holds deep and sustained spiritual value for those individuals. In recognizing this democratic, non-elitist, independent-minded definition of a contemporary pilgrimage destination, it seems appropriate that it is approached through the lenses of collaborative map-making which is equally non-elitist and independently defined.

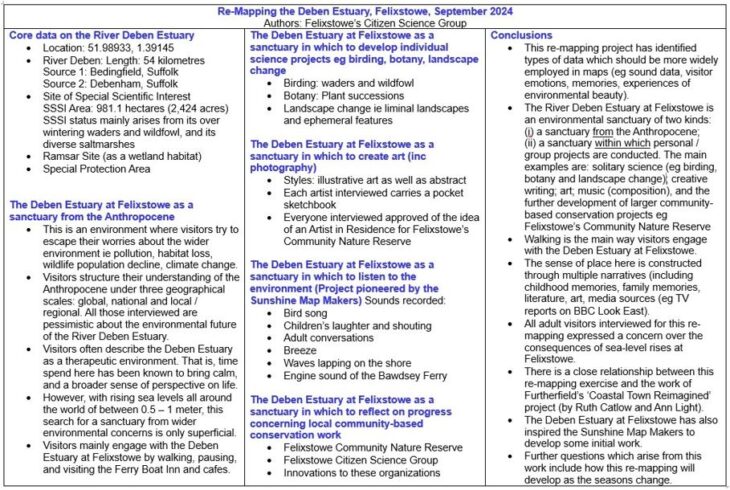

The first re-mapping of the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe which was completed by FCSG is included below:

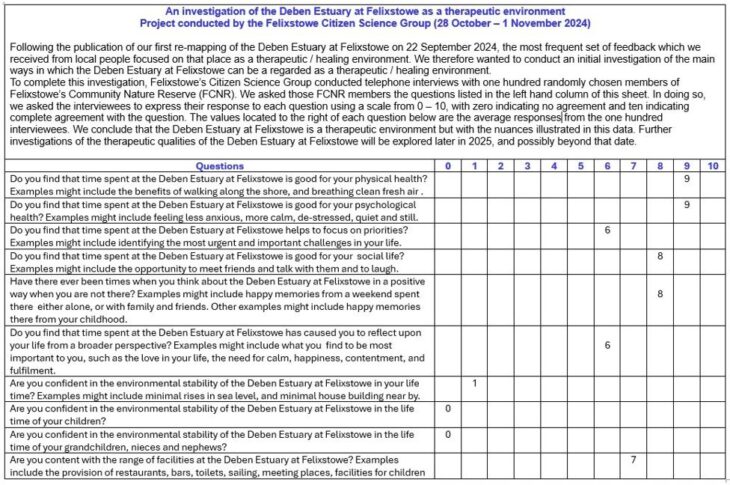

This map led to further published work by FCSG on the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe as a Therapeutic Environment and is included below:

Part 4

The evolution of this collaborative map making exercise in the River Deben Estuary at Felixstowe took place during the last six months of 2024. It began with the realization that this chosen ecosystem is liminal. That discovery began in July 2024. From reading parts of Turner (1969) members of FCSG began to understand liminal environments from a social and cultural perspective. This aspect of liminality particularly appealed to those members of FCSG who identify as LGBTQ+.

Equally, the discovery of Relph (1976) was a second stage in the evolution of FCSG’s collective thinking about their re-mapping of the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe. Specifically, Relph focused on contemporary ways of exploring place and placelessness (as problematic, illusive and ambiguous ways of appreciating liminal spaces). Again, ideas of ambiguous geographic identity appealed to the LGBTQ+ members of FCSG as well as other members from a Humanities background. Members of FCSG with a more mainstream scientific background began to engage with the intellectual challenges of mapping geographic features which have liminal characteristics. Those challenges of wrestling with the cartography of liminal and therapeutic environments continue at the time of writing.

Part 5

The questions which currently occupy FCSG debate on their collaborative map making of the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe may be summarized as follows:

(i) Which geographic and ecological features should be included in any collaborative map making exercise of a liminal and therapeutic environment, such as the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe? .

(ii) Alongside question (i), there is discussion over which attributes of those features should be included.

(iii) How can data quality be maintained in this type of map making?

(iv) What are the broader data management problems which need to be addressed?

(v) What are the risk management problems?

(vi) How will the answers to these first five questions change through the seasons, and as a consequence of tidal change?

(vii) Can the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe be considered as a local pilgrimage destination?

(viii) If so, how might that status affect the development of collaborative map making in this environment?

(ix) How can the FCSG collaborative maps of the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe be shared with a wider audience?

(x) How can feedback from that dissemination be incorporated into future iterations of FCSG’s collaborative map making?

Conclusions

The River Deben Estuary at Felixstowe has clearly been recognized by FCSG members as a sanctuary with two important aspects. First, it is a sanctuary from routine family and work-related pressures. Second, it is a sanctuary within which an evolving range of individual and small-group projects are developing. In this way, the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe can be recognized as a multi-project environment: ie it is an area which has inspired a broad range of individual and small-group projects, ranging across the Arts and Sciences.

Collaborative map making has undeniable political dimensions. It is defiant through its refusal to passively accept mainstream elitist maps as being the ultimate authority in the cartography of ecosystems which are of significant local importance. However, collaborative map making is also cooperative because it does not seek to replace those mainstream maps. Instead, it seeks to create new maps which will hopefully be aligned with mainstream geographic and ecological research.

Creative tensions will almost certainly persist within FCSG’s collaborative map-making activity. These include the following:

(i) The Deben Estuary at Felixstowe is simultaneously a public space, but also a private space for personal reflection.

(ii) It is an ancient environment, having been created during the last Ice Age, but it is also a contemporary environment, bearing the imprint of contemporary weather patterns, sea level rises, pollution and other examples of human impact.

(iii) The estuary fascinates many of its visitors. However, it also fills some of them with fear eg there are ‘No Swimming’ signs along the shore line.

(iv) People of faith have been recorded as describing the Deben Estuary at Felixstowe in transcendent terms, such as “Heavenly”, “Blessed”, “Sacred” and “God-given”. However, at the same time, every aspect of this environment has thoroughly immanent characteristics. The alignment of transcendence and immanence is therefore a challenge which may never be easily recorded on a map, unless it is simply noted in a map’s margin or footnotes as being a feature which causes concern.

(v) Leading on from (iv) above, many of the discussions by people of faith regarding their sense of place at the Deben Estuary draws from Biblical and other ancient scriptures. However, alongside those narratives of continuity, there are also narratives of unsettling change, such as the presence of pollution, sea level rise and adverse weather conditions.

Further discussion of these questions will be published here when they are developed.

References

Andrews H, and Roberts L (eds) (2014) Liminal Landscapes: Travel, Experience and Spaces in-between.

Cooper AR (2000) Places of Pilgrimage and Healing (Capall Bann).

Cooper AR (2019) Therapeutic Walking on the Antarctic Peninsula, published in Kindred Spirit, November / December, pages 39 – 41.

Cooper AR (2020) Therapeutic Walking along the Yangtse River, China, in the Art of Healing, vol 2, Issue 71, pages 38 – 41.

Macfarlane R (2012) The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot.

Macfarlane R (2015) Landmarks.

Relph E (1976) Place and Placelessness.

Shields R (2002) Zones of Transition.

Solnit R (2001) Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Penguin.

Tuan YF (1974) Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Values

Turner V (1969) The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure.