Written by NBN Trust CEO, Lisa Chilton

In this monthly (or thereabouts) Nature Positive blog, I’m going to share happy tales from the UK’s biodiversity community. Little snippets of joy to inspire, uplift and remind us of what it’s all about.

One of the stories that brought a smile to my face over the festive period was from Scarborough, where the arrival in the harbour of ‘Thor’, a young Walrus, became a huge attraction. Thousands of people flocked from near and far to get a glimpse of this rare visitor from the Arctic. A police cordon was set up on the harbourside to manage the crowds, and British Divers Marine Life Rescue (BDMLR) maintained a round-the-clock watch. Though there were a few instances of bad behaviour, BDMLR reported that most people were “immeasurably respectful to our visitor” and expressed “their appreciation of Thor being protected”. With Thor still lounging on the seafront on New Year’s Eve, Scarborough Borough Council took the laudable decision to cancel the town’s fireworks display. Thor eventually slipped back into the sea, stopping for a rest in Blyth on the Northumberland coast, before heading off once more.

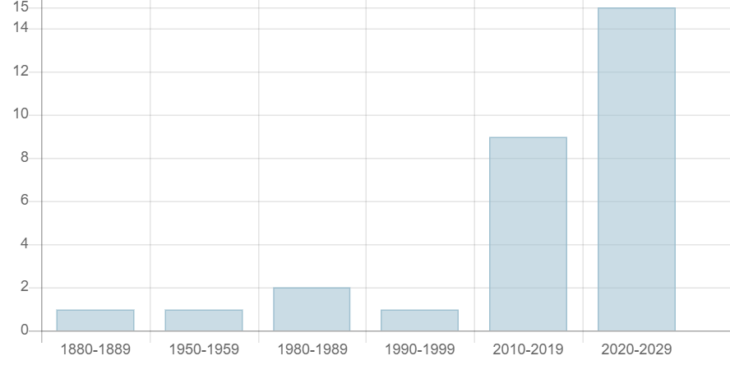

Thor’s brief visit brought happiness to countless people, but what do we know about Walruses in the UK? There are 31 records of Walrus sightings on the NBN Atlas, the UK’s largest publicly accessible database of wildlife records. The oldest record, shared with the NBN Atlas by the Bristol Regional Environmental Records Centre, dates from 1839. A juvenile Walrus was spotted in the Severn Estuary, where it swam upstream as far as Purton (close to what is now the Wildlife and Wetland Trust’s Slimbridge reserve). No cute name or happy ending for this one though, as it was promptly shot. In 1884, a Walrus was seen in Bute, and in 1954 one visited my local beach, Collieston, on the Aberdeenshire coast. Sightings really picked up in the 2000s, though, as you can see from the graph below. This may well reflect a growth in the collection of records rather than rising numbers of Walruses visiting our coasts. Also, the sightings typically occur in clusters (notably in Scotland in 2018 and Wales in 2021), reflecting multiple sightings of the same Walrus rather than lots of different animals. Records of Thor have not yet made their way to the NBN Atlas, but sightings and photos of him have been added to iNaturalistUK, and more may follow.

Number of Walrus records by the decade in which they’ve been recorded (NB only decades with records are shown, not the intervening decades). Data from NBN Atlas.

Which begs the question: why are these wandering ‘tooth-walkers’ (from their scientific name, Odobenus) visiting the UK? Walruses are highly social animals, living in large herds in their Arctic home. Are our visitors lost, sick, or blown off-course by a storm? Is their behaviour being affected by climate change and the loss of sea ice? Or are they simply young explorers, venturing forth before settling into a breeding herd?

Back to Thor though, it’s heartening to see how a wandering marine mammal can so lift our spirits. And it’s inspiring to reflect on the records of these rare visits, collected by diligent volunteers over the centuries. Would they ever have considered that we’d be looking at these records in 2023? And who’ll be reading the records of Thor’s antics in centuries to come? We can all play a part in collecting the records that future generations will look back on to understand – and hopefully track the recovery – of our wonderful wildlife.