Written by Dr Adrian Cooper, Felixstowe Citizen Science Group

This discussion is presented in five parts. First, I will provide a background to this discussion, including its research group. Second, an explanation will be provided regarding data collection, data management and data modelling. Third, the motivations for climate activism are identified relevant to the stakeholders in this project. Fourth, examples of relevant climate activism are identified. Finally, future questions are considered, including the use of enhanced inclusiveness among women, young people aged 18 – 25, and people of faith. The overall aim of this discussion is to explore the ways in which climate activism in the Felixstowe area is inspired, developed and expressed. It is hoped that this work will inspire other communities to also develop an agenda of climate activism.

Part 1: Background

This project was developed by the Felixstowe Citizen Science Group (FCSG). They were founded in April 2018 with the principal aim of conducting impact analyses on their local community nature reserve. However, in addition to that core activity, FCSG has addressed a broad range of other citizen science projects. Their Facebook page shows that work. Throughout 2025, FCSG has become increasingly interested in climate activism and the ways it is inspired by greatly valued local environments. Most of the work this year has focused on the River Deben estuary and Landguard Nature Reserve in Felixstowe, UK. Both those environments have been appreciated by research interviewees as therapeutic environments. For local people of faith, they are also widely regarded as local pilgrimage destinations i.e. locations where those individuals can reflect, meditate and / or pray to their chosen deity.

The River Deben estuary is also recognised here as a liminal environment. That is, it is constantly in transition as a consequence of tides, seasons and weather. The estuary is also appreciated as a sanctuary away from the causes of stress and anxiety. Equally though, it is seen as a sanctuary within which scientific, creative and community-based activities can be reflected upon and developed.

Part 2: Data collection, modelling, management and modelling

The River Deben estuary and Landguard Nature Reserve in Felixstowe are recognised by FCSG as examples of complexity. That is, they are environments which are appreciated by FCSG as being complex systems with many interconnected parts, non-linear relationships, feedback loops, emergent properties, and adaptation / evolution. Visitors to these environments also recognise their ecological features, as well as their social, cultural, aesthetic, psychological and spiritual dimensions. FCSG therefore adopts a Systems Thinking approach to those complex environments (Ramage and Shipp 2009).

A combination of ethnographic interviews and telephone interviews has been employed by FCSG throughout their research (Cooper 2025). The benefit of doing so has been to try and achieve a depth and breadth of understanding. Interviewees for both methods have been randomly selected from the 1,700 membership of Felixstowe’s Community Nature Reserve. Ethnographic interview groups have never exceeded twelve members. Those ethnographic interviews are conducted during guided walks which have taken place, at least once a month, since the start of 2025. Telephone interviewees have averaged one hundred randomly chosen individuals. Regarding those telephone interviews, 25 members of FCSG volunteer to each contact four nominated interviewees – the contact details for whom are allocated to them by FCSG leaders. In that way, a sample of 100 telephone interview responses are quite easy to organise within no more than five working days. The results of both forms of data collection are added to a shared document on One Drive cloud storage service.

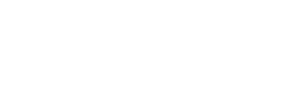

An example of telephone interviews in this context may be taken from the beginning of 2025:

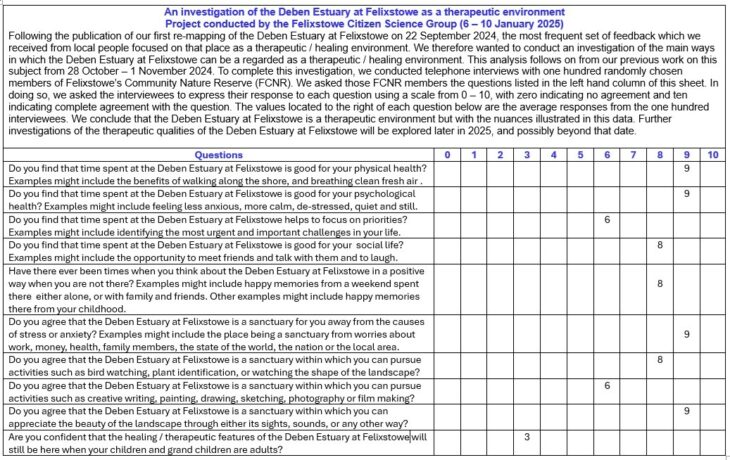

Telephone interviews with people of faith concerning experiences of local pilgrimage destinations may be illustrated with an example from February:

Ten forms of AI have been used to enhance the experience of taking part in the guided walks. They are: (i) Windy.com (for weather and climate modelling); (ii) ClimateCentral.org (also for climate change including sea level rise and coastal flood risks); (iii) Merlin Bird ID (for bird identification from sound, but also pictures); (iv) iNaturalist (for plant identification); (v) Seek by iNaturalist (for younger people); (vi) Pl@antNet (also for plant identification); (vii) GlobalForestWatch.org (for changes in land use); (viii) NASA World View; (ix) Google Earth; (x) Zooniverse for global comparisons.

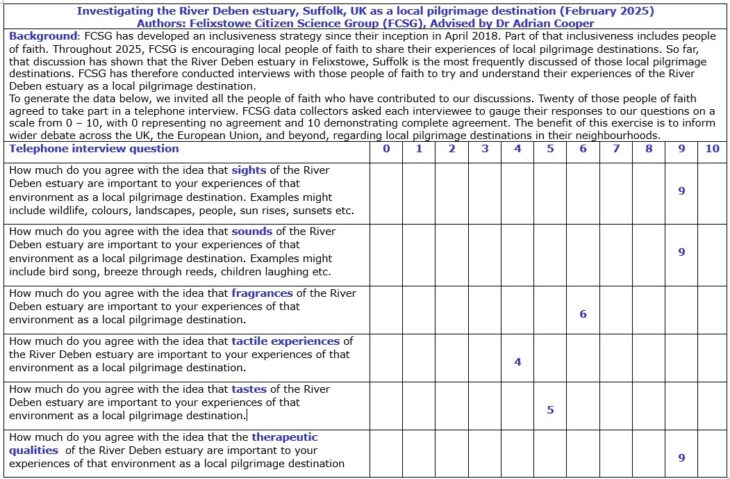

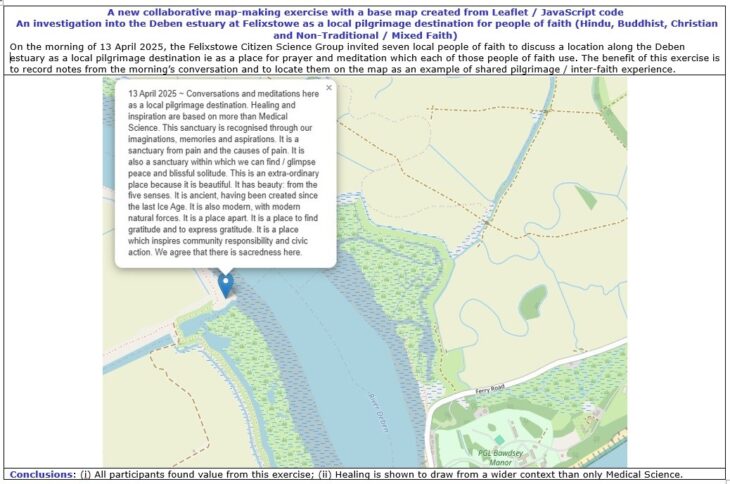

Basemaps for the collaborative map making have always been created using Leaflet (JavaScript Library). This has aligned FCSG’s work with other forms of Geographical Information System (Longley et al, 2015; Bolstad, 2022; and Bernhardsen, 2002). However, while other forms of GIS develop their work using layers, FCSG has consistently felt frustrated in not being able to find layers which accommodate the multiple data types which their research encounters. That is because FCSG deals with ethnographic data which includes experiences drawn from the five physical senses: sight, sound, fragrance, touch and taste. In addition, FCSG has encountered significant discussion among interviewees on therapeutic aspects of local environments. Among people of faith, FCSG has encountered discussions of locations which have been described in terms of them being local pilgrimage destinations. To overcome these frustrations among FCSG with the limitations of current GIS facilities (eg Arc GIS and QGIS), they choose to locate their base maps surrounded by side panels of information relevant to each data type. An example from March 2025 illustrates this form of presentation:

A different form of presentation with ethnographic data on local pilgrimage destinations may be taken from work in April 2025:

Part 3: Motivations to take part in local climate activism

Data collected from ethnographic interviews and telephone interviewees identified five sets of motivation among people in the Felixstowe area to participate in community-based climate activism. These may be summarised as follows:

- Scientific motivations – Although no interviewees used the term ‘Anthropocene’, it is clear from their discourse that they are significantly aware of the following environmental problems. It is equally clear that these problems motivate participation in local climate activism: (i) biodiversity loss; (ii) alterations to biogeochemical cycles (eg carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles); (iii) changes to soil and atmospheric chemistry; (iv) land-use changes; (v) the accumulation of human-made materials (eg plastic, metal, concrete and glass); (vi) techno fossils (eg plastic particles, aluminium and synthetic chemicals); (vii) global infrastructure networks (eg roads, cities and data systems); (viii) Pollution (eg air, water, soils, persistent organic pollutants, heavy metals); (ix) geological and stratigraphic markers (eg black carbon from fossil fuel combustion); (x) Ocean acidification; (xi) Feedbacks (eg melting permafrost releasing methane which amplifies human influence).

- Aesthetic motivations – Research interviews also showed that interviewees felt motivated to take part in local climate activism because they felt the environmental beauty of the River Deben Estuary and Landguard Nature Reserve is under threat. When these interviewees talk about environmental beauty, they do so consistently with reference to sights, sounds, fragrances, touch and taste experiences.

- Community-building and educational opportunities – Interviewees also described the River Deben estuary and Landguard Nature Reserve as “community-resources” for walking, education, family events, creative writing, art, music composition, individual scientific projects (eg bird watching and recording, botany, finding evidence of the Anthropocene) and citizen science. Again, where these environments are viewed in this way, and environmental threats are also appreciated, motivation to take part in local climate activism is inspired and increased.

- Therapeutic motivations – The River Deben estuary and Landguard Nature Reserve are consistently recognised among interviewees as being places of healing – both for mental and physical health challenges. From the ethnographic interviews, it has been possible to unpack interviewees’ ways of defining therapeutic environments:

(i) Physical characteristics – places where people feel safe, comfortable and calm.

(ii) Emotional characteristics – places which people trust and which will always be accessible to them.

(iii) Social characteristics – places where helpful, intimate and confidential conversations can take place.

(iv) Psychological characteristics – places which help to boost self-esteem and dignity.

(v) Holistic characteristics – where the mind, body and spirit can feel restored.

Once again, when interviewees recognise that their favoured therapeutic environments are threatened, they feel more motivated to take part in local climate activism. Further discussion of therapeutic environments may be found in Cooper (2000).

- Local pilgrimage destinations – FCSG is aware of the need to develop its inclusiveness agenda. This is mainly because the Felixstowe population is becoming increasingly cosmopolitan. FCSG also recognises that contributions from its inclusiveness agenda greatly enrich the research interview data. At present, FCSG focuses on reaching out to women, young people between 18 – 25, and people of faith. Within those three categories, people of colour and members of LGBTQ+ communities are also included. However, at the time of writing no people of colour or LGBTQ+ individuals have wanted to be defined primarily and exclusively in that way. Instead, they have asked to be thought of either as women, youth or people of faith. Among these people of faith, the River Deben estuary and the Landguard Nature Reserve are described through a spectrum of religio-geographical values ranging from “special”, “very special”, “extraordinary”, and “sacred”. Against that background, the river estuary and Nature Reserve have become places for reflection, meditation and prayer. Significantly, the focus of those practices is most frequently on environmental beauty (ie defined using the five physical senses), gratitude to their chosen deity, and a motivation to take part in civic activities such as climate activism. Further discussion of local pilgrimage destinations may be found in Cooper (2000).

Part 4: Examples of local climate activism

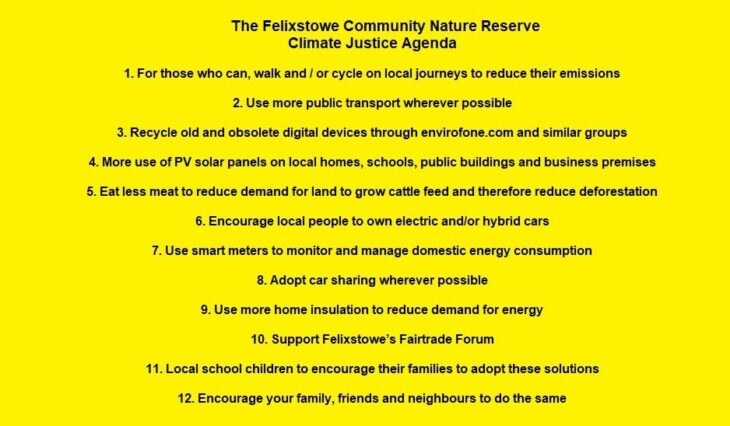

Community-based climate activism began in the Felixstowe area in September 2021 when questions were asked of Felixstowe’s Community Nature Reserve about their willingness to develop a climate justice agenda. Between that beginning and July 2022, a Climate Justice Agenda was developed using ideas suggested by local people in the Felixstowe area. This Climate Justice Agenda may be summarized as follows:

The Climate Justice Agenda was launched at a march along Felixstowe sea front on 2 July 2022 (Cupriak, 2022).

A series of additional community-based climate activism projects is described by Rackley (2025).

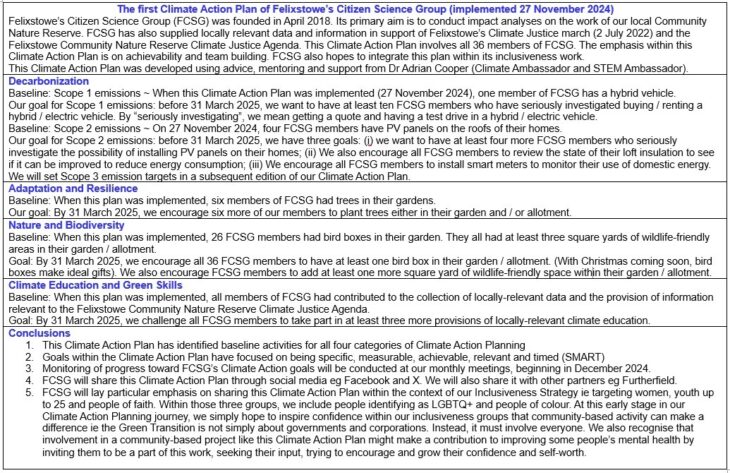

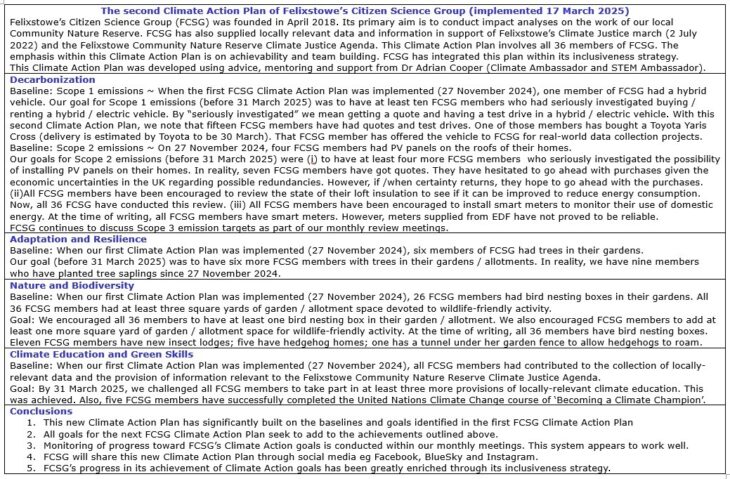

Within FCSG, members have developed two Climate Action Plans as follows:

These examples of climate activism have been reinforced through further collaborative map-making exercises such as the following from June, July and August 2025:

Part 5: Future questions

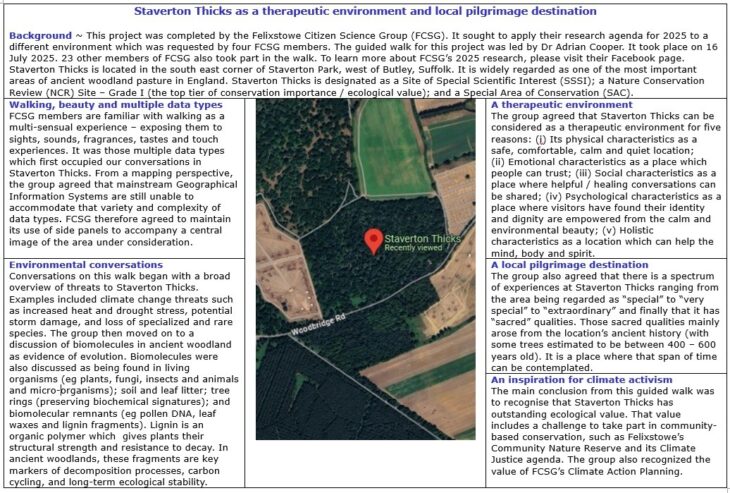

This research into motivations among people in the Felixstowe area to participate in community-based climate activism will continue into 2026 and beyond. The main difference between that future work and the research conducted in 2025 will be to locate the research in new locations to test whether the integrity of the five sets of motivation will remain in tact. Preliminary work at a location which is away from the River Deben estuary and the Landguard Nature Reserve took place in July 2025. It is summarised here:

A further development in the 2026 research will be more emphasis on inclusiveness, with particular reference to the contributions of local women, young people aged between 18 – 25, and people of faith. It is acknowledged here that enhanced inclusiveness in this work greatly enriches the data drawn from ethnographic and telephone interviews. When this new research is developed, it will be featured on the FCSG Facebook page. Discussions of that work will also be submitted to the NBN Trust and the European Citizen Science platform for wider debate. It is hoped that other groups will feel encouraged to adapt these ideas for their local communities.

Conclusions

- A clear set of five motivations has been discovered by FCSG concerning local people’s motivations to support community-based climate activism.

- Collaborative map making is an effective way to summarize experiences of the River Deben Estuary and Landguard Nature Reserve.

- Artificial Intelligence and Geographical Information Systems have been confronted by FCSG for their limitations in the type of information provided, and their trend toward reductionism. FCSG has therefore tried to overcome that reductionism by using side panels alongside its base maps to enrich its collaborative map making.

- The guided walks which under lay the data collection process expose participants to multi-sensual experiences (ie sights, sounds, fragrances, touch and taste).

- The mixed methods of ethnographic interviews and telephone questionnaires is an effective contribution to understanding motivations to take part in climate activism.

- Inclusiveness (eg among women, young people and people of faith) significantly enriches the data collection.

- This work will continue into the foreseeable future using other local environments (eg Trimley Marshes Nature Reserve).

References

Bernhardsen, T (2002) Geographic Information Systems: An Introduction

Bolstad, P (2022) GIS Fundamentals: A First Text on Geographic Information Systems

Cooper, AR (2000) Places of Pilgrimage and Healing (Capall Bann Publishing)

Cooper, AR (2025) Investigating Therapeutic Landscapes and Local Pilgrimage Destinations, (online) https://youtu.be/ngSSUKZ7dpg

Cupriak, A (2022) Hundreds gather to share solutions at town’s first climate march (online) https://www.eadt.co.uk/news/20699659.hundreds-gather-share-solutions-towns-first-climate-march/

Longley PA; Goodchild MF, Maguire DJ, and Rhind DW (2015) Geographic Information Systems and Science

Rackley KM (2025) Interview with Dr Adrian Cooper (podcast, on line) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J1aVRwGYIUg (Accessed 4 August 2025)

Ramage M and Shipp K (2009) Systems Thinkers (Springer, London and New York)