Blog written by Dr Nick Fraser, Head of Department of Natural Sciences at National Museums Scotland.

With an estimated accumulated total of over 3 billion specimens, the vast array of natural science collections in museums all over the world represent a rich, powerful, but only partially untapped database. Worldwide, natural science collections date back to the 17th Century and, with their associated collection data, can be an invaluable resource for reconstructing and monitoring historical and current changes in species distribution. As a consequence, great efforts are currently being made to aggregate these together in a digital format with major programmes such as IDigBio and DiSSCo.

Beetles from National Museum Scotland Dufresne collection, 1700s

These integrated approaches are being hailed as incredible resources to scientists, policy makers, governments and the general public alike. Information about such critical environmental issues as the spread of invasive species, the changing distribution of vectors of disease, or the alteration in flowering times and appearance of pollinating species can be gleaned and mobilised from these aggregated databases.

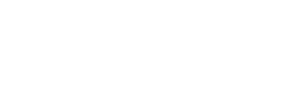

Primula scotica. Credit: Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh

But if the data from collections can be so valuable, how much more powerful will the significantly greater number of observational records from biological recorders from around the world be, especially if linked with the voucher specimens in recognised natural science collections?

This is exactly what the Review of the Biological Recording Infrastructure in Scotland is proposing.

First and foremost it outlines a coherent and uniform approach to biological recording in Scotland and potentially the entire UK. Built on an in-depth consultation with a broad range of organizations and individuals involved in biological recording and the endeavour to gain a better understanding of biodiversity, the Review provides a very tangible roadmap towards building and maintaining a comprehensive database of Scotland’s Biological records. It also signposts how this can be linked to the collections databases of museums and herbaria through the NBN Atlas Scotland and thereby link current recording to collecting over the past 300 years or more.

Kristine Bogomazova, Loch Tarbert. Credit: Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh

Although ambitious, the plan advocates an effective biological recording infrastructure. It would undoubtedly contribute significantly to the biodiversity evidence base necessary for environmental decision-making, from land use and planning through to climate change mitigation, species and habitat protection and management of Scotland’s natural capital.

We should all be excited by the opportunities this will bring for a much better understanding of Scotland’s biodiversity and monitoring it for the future.

What a powerful tool this will be.